Sometimes drawing comes easier than writing. Words have to mean something to be something. There are rules and conventions which must be respected (or at least willfully rejected) if connection to a broad audience is to be the goal.

Sometimes drawing comes easier than writing. Words have to mean something to be something. There are rules and conventions which must be respected (or at least willfully rejected) if connection to a broad audience is to be the goal.

Words have a public function. Although we could go on here about the necessity of a well-curated vocabulary for mental clarity, feelings and urges and gut-pains need not be pressed into poetry to get us through the day. We only need words when we hope to transmit from one mind to another, as a subtler tool than fists and spit.

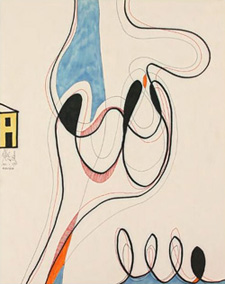

So when pen hits paper and lines start to appear, I lazily drift off from legibility after a few syllables. My nub prefers to circle and underline and star instead of coming up with better terms to nail down my thinking. Why write “buy milk” when a dollar sign and carton will do? Why go to the trouble to write “urgent” when I can channel my stress into a series of underlines that bury down to the bottom of the page?

And if a drawing begun falls so short of the mark as to be unrecognizable, I can term it an abstract, decide it’s no more than a “graphic element,” and guiltlessly throw it away. Not so with words. Once typed, once spoken, once tweeted to the world they live on to be mistaken and misconstrued, as often to my benefit as not.

And if a drawing begun falls so short of the mark as to be unrecognizable, I can term it an abstract, decide it’s no more than a “graphic element,” and guiltlessly throw it away. Not so with words. Once typed, once spoken, once tweeted to the world they live on to be mistaken and misconstrued, as often to my benefit as not.

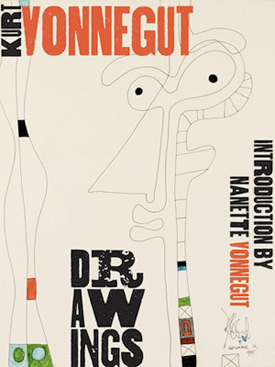

My guess is that Kurt Vonnegut knew this crisis on occasion too. Felt the weight of words to be too great, craved the ambiguity of the sketchbook where the question “What do you mean?” can be left open-ended, unanswered without one seeming dim.

My guess is that Kurt Vonnegut knew this crisis on occasion too. Felt the weight of words to be too great, craved the ambiguity of the sketchbook where the question “What do you mean?” can be left open-ended, unanswered without one seeming dim.

Recently, Vonnegut’s many sketches have been collected by his daughter, Nannette. The collection moves through Vonnegut’s entire career – from early scribbles that wiggled their way into his novels, to his later work that took on a life of its own. Interesting stuff, regardless of which way your ink decides to flow.